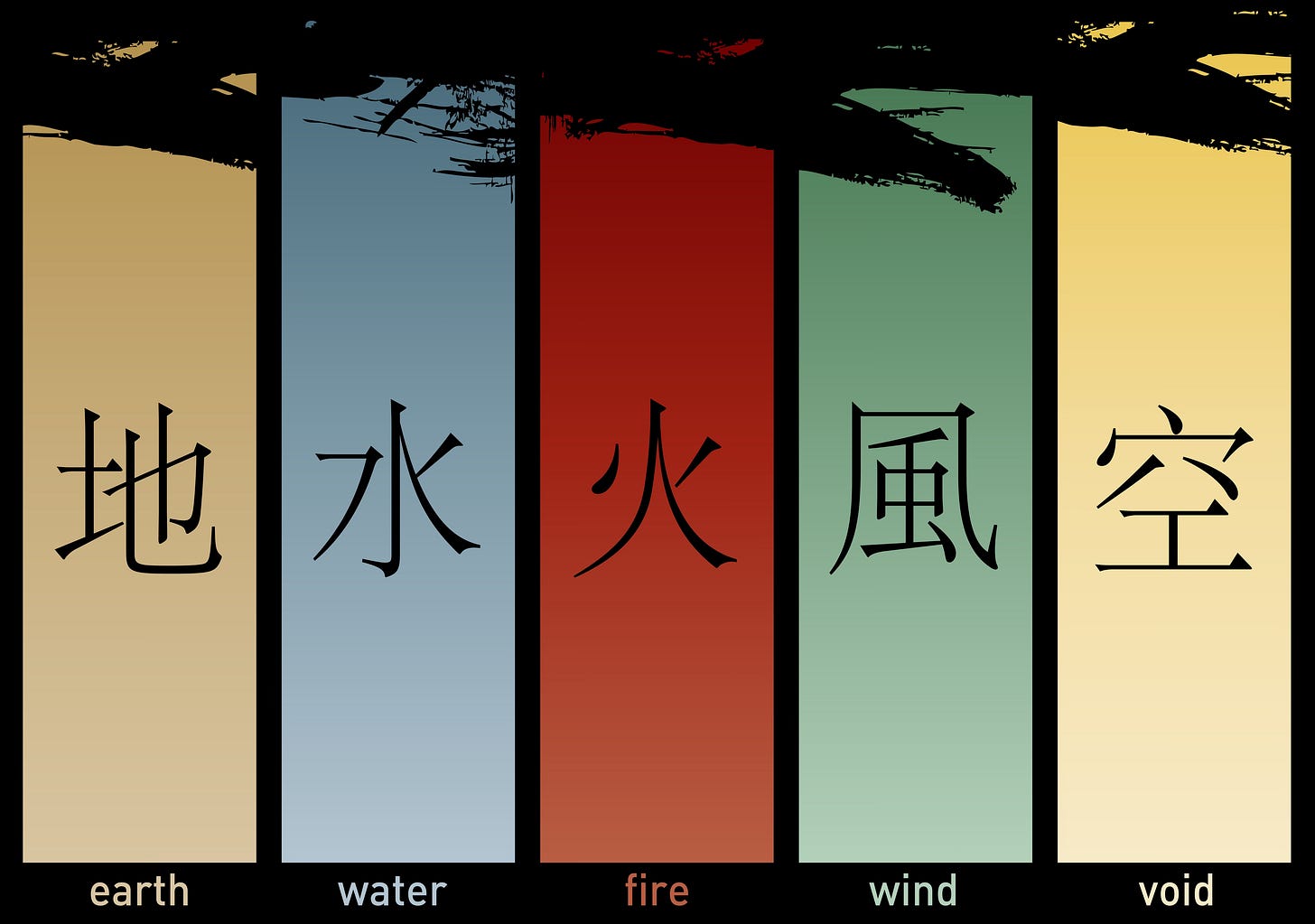

The GoDai: Five Great Elements in Japanese Philosophy

Understanding the Five Greats

In Japanese philosophy, the concept of GoDai (五大, literally “Five Greats”) provides a framework for understanding both the natural world and the inner life of human beings. Rooted in Buddhist cosmology, influenced by Chinese thought, and refined within Japanese culture, the GoDai describe five fundamental elements: Earth (地, Chi), Water (水, Sui), Fire (火, Ka), Wind (風, Fū), and Void (空, Kū).

Unlike the Western four-element model of Earth, Water, Air, and Fire—popular in Greek philosophy—the GoDai introduces a fifth principle, the Void (Kū), emphasizing emptiness, potentiality, and unseen forces. These five elements are not literal substances but symbolic archetypes describing qualities of matter, energy, behavior, and spirit.

Understanding the GoDai means exploring how the Japanese conceptualized harmony between nature, body, and mind. These five “greats” have shaped Buddhist ritual, martial arts, aesthetics, and even modern psychology.

Origins and Influences of the GoDai

The roots of the GoDai lie in Indian Buddhist thought, particularly the Mahābhūta, the “great elements” of earth, water, fire, air, and space (Harvey, 2013). When Buddhism traveled to China, these ideas merged with Daoist cosmology and the Five Phases (Wu Xing) system. By the time Buddhism entered Japan in the 6th century, these cosmological models were adapted into the Japanese worldview.

In Japan, Shingon Buddhism—founded by Kūkai (774–835)—played a central role. In his writings, Kūkai explained that the universe itself is composed of the five elements, which also constitute the human body and mind. For him, the Void (Kū) was not a negation but the fertile emptiness (śūnyatā) from which form and meaning arise (Shōrai Mokuroku, Kūkai, trans. Hakeda, 1972).

The GoDai also found expression in esoteric Buddhist mandalas such as the Taizōkai (Womb Realm) and Kongōkai(Diamond Realm), where the five elements form the basis for meditative visualization and ritual practice (Abe, 1999).

The Five Greats Explained

1. Chi (地) – Earth

Chi represents solidity, stability, and grounding. It corresponds to physical matter, the body, and all enduring structures.

In human life, Chi symbolizes stability of mind and perseverance. In martial arts, it is the rooted stance, immovable and strong. Miyamoto Musashi, in The Book of Five Rings (Go Rin no Sho), described Earth as the foundation: “The Earth book is about strategy based on the nature of solid ground” (Musashi, 1645/1974).

In Japanese aesthetics, stones in Zen gardens represent Chi—embodying permanence amid impermanence.

2. Sui (水) – Water

Sui symbolizes adaptability and flow. Water is soft, yet it can erode mountains; it adjusts to its container yet never loses its essence.

In the body, Sui corresponds to fluids and circulation. Psychologically, it represents emotions, intuition, and adaptability.

In martial practice, Sui reflects the principle of yielding and redirecting an opponent’s force, seen in aikidō and ninjutsu. Musashi emphasized flexibility in his Water Book: “The spirit must be like water. Water adopts the shape of its vessel, sometimes a trickle, sometimes a torrent” (Musashi, 1645/1974).

Culturally, water in Japanese poetry—such as Bashō’s haiku on flowing rivers—embodies impermanence, echoing the Zen teaching that no moment repeats.

3. Ka (火) – Fire

Ka stands for energy, transformation, and passion. Fire creates light and warmth, but it also destroys.

In the human sphere, Fire represents vitality, willpower, and creativity. It corresponds to metabolism in the body and the burning force of transformation in the spirit.

In martial arts, Fire is decisive action—swift strikes and bold offense. Musashi wrote: “In battles, speed is the essence of fire… fire is fierce and fast” (Fire Book, Musashi, 1645/1974).

Artistically, fire’s intensity is seen in kabuki theater and in calligraphy styles that emphasize bold, dynamic strokes.

4. Fū (風) – Wind

Fū symbolizes movement, freedom, and expansion. Wind is unseen but felt, carrying seeds, scents, and change.

In the body, Wind relates to breath and nervous energy. Psychologically, it corresponds to knowledge, openness, and curiosity.

In martial contexts, Fū is agility, unpredictability, and adaptability. Musashi’s Wind Book emphasized knowing the strategies of others: “To know the way of others is to know the wind” (Musashi, 1645/1974).

Culturally, wind embodies transience in Japanese aesthetics—the rustling bamboo, the fleeting cherry blossoms scattered by a breeze. In haiku, wind often signals both impermanence and subtle insight.

5. Kū (空) – Void

The most profound of the five, Kū (Void) signifies emptiness, potentiality, and the ineffable. It does not mean nothingness but rather the emptiness full of possibility, akin to Mahayana Buddhism’s śūnyatā.

Kūkai emphasized that the Void is the ground of awareness and creativity: “From emptiness, form arises, and in form, emptiness is realized” (Shōrai Mokuroku, Kūkai, trans. Hakeda, 1972).

In martial arts, Void represents mastery beyond technique, acting spontaneously without hesitation. Musashi described it as the ultimate stage of strategy: “By knowing things that exist, you can know that which does not” (Void Book, Musashi, 1645/1974).

In art and design, Kū is embodied in the use of empty space (ma), which gives form meaning and balance.

The GoDai in Japanese Culture

Religion and Ritual

The GoDai appear in gorintō (五輪塔), five-tiered stone stupa monuments used in cemeteries and temple grounds. Each tier represents one element, ascending from Earth to Void. These structures symbolize the return of the human body to the five elements upon death (Deal & Ruppert, 2015).

Martial Arts

The GoDai form the structure of Musashi’s Go Rin no Sho (1645), one of Japan’s most famous martial treatises. Beyond Musashi, ninjutsu schools have used the GoDai to train mental states and strategies—teaching practitioners to embody stability (Earth), adaptability (Water), aggression (Fire), agility (Wind), and spontaneous creativity (Void).

Aesthetics and Everyday Life

Japanese aesthetics integrate the GoDai in subtle ways:

Chi in rocks and architecture.

Sui in flowing streams of gardens.

Ka in firelit festivals and theater.

Fū in poetry and fleeting seasonal changes.

Kū in the open spaces of tea rooms and Zen paintings, where emptiness invites imagination.

Modern Interpretations of the GoDai

Today, the GoDai framework is used in psychology, leadership, and personal growth (Lowry, 2006). Each element can be seen as a personality archetype or inner resource:

Earth (Chi): Grounding and stability.

Water (Sui): Emotional flexibility.

Fire (Ka): Passion and drive.

Wind (Fū): Curiosity and learning.

Void (Kū): Creativity and transcendence.

Mindfulness practices in Japan often integrate elemental meditation, inviting practitioners to balance these qualities within themselves.

Living with the Five Greats

The GoDai are more than a cosmological model; they are a guide to life. They remind us to be steady like Earth, fluid like Water, passionate like Fire, agile like Wind, and open like the Void.

By integrating these archetypes, one lives in harmony with the natural rhythms of existence. In a fragmented modern world, the GoDai offers a timeless vision: that we are not separate from nature, but part of a dynamic interplay of form and emptiness, stability and change, matter and spirit.

Like what you read? Keep exploring…

If this post resonated with you, you’ll love my book:

An Uncarved Life: A Daoist Guide to Struggle, Harmony, and Potential

This book blends timeless Daoist wisdom with real-world insight into how we can navigate struggle, cultivate inner peace, and live in alignment with our deeper potential. Drawing from classical texts like the Dao De Jing and integrating modern psychology and neuroscience, An Uncarved Life offers a grounded, poetic, and deeply personal guide to living well in a chaotic world.

Whether you’re seeking clarity, calm, or a more meaningful path forward, this book is a companion for anyone who wants to walk the Way with sincerity and strength.

Available now in print, Kindle, and audiobook formats.

Click here to get your copy on Amazon

References

Abe, R. (1999). The Weaving of Mantra: Kūkai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press.

Deal, W. E., & Ruppert, B. (2015). A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism. Wiley-Blackwell.

Hakeda, Y. (Trans.). (1972). Kūkai: Major Works. Columbia University Press.

Harvey, P. (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Lowry, D. (2006). The Essence of Budo: A Practitioner’s Guide to Understanding the Japanese Martial Way.Shambhala.

Musashi, M. (1645/1974). The Book of Five Rings (T. Cleary, Trans.). Shambhala.

Thank you for sharing this reflection on GoDai. I also explore how these five elements connect with space and stillness in daily life — your words reminded me of that balance.